This is an interesting article from the December, 1940 Along the Line.

8 ½ Miles Jointless Rail Now In Track

''What makes The Bankers so late this morning?"

The query was addressed to the information clerk at Hartford

station by a man who had just come from the subway passage under the tracks.

"It wasn't late," was the reply. "It left here

five minutes ago."

"Good gosh!" the man exclaimed, "I've been

standing there in the subway for over ten minutes and I never even heard it!"

And thereby hangs a tale.

He was one of our regular commuters, and had formed the

habit of waiting in the subway, reading his paper, until he heard the vibration

when his train headed in on the station viaduct. But this particular morning

there was no noticeable vibration. Nor has there been since. And welded rail is

the answer.

The Hartford station viaduct is equipped with jointless

welded rails, each 840 feet in length. This was the New Haven Railroad's first

experiment with this new development in track construction and it has proved

eminently successful. It has been followed by additional installations

elsewhere and in all likelihood the future will see much additional track butt

welded to form continuous rails of a thousand or more feet in length.

We now have altogether a total of 45,106 feet, or about 8-1/2 miles of welded rail in place, on bridges, through stations and grade

crossings, and tunnels. Bridges were chosen for first installation because of

the elimination of vibration through elimination of the impact at joints, with consequent

lessened wear and tear on the bridge structure. Grade crossings and stations

were next chosen because the expense of maintaining joints is greater in those

places; at crossings it involves tearing out and replacing- part of the roadway

material: and at railroad stations it often involves tearing out and replacing

portions of polatforms.

The longest stretch of welded track which has yet been laid

on the New Haven is 3,600 feet through the Terryville tunnel. This was welded

at Bridgeport yards into 1,200-foot sections and these field-welded in the

tunnel to make continuous rails from one end of the tunnel to the other without

a break.

The longest single stretch which has been welded and moved

in one section to date was 1,421 feet for each of the two rails for Track 2

through the Fair Haven tunnel, while two 1,407-foot rails were placed in Track

1 at the same location. These were welded at the Bridgeport yard and moved on

flat cars to the tunnel.

A close-up inspection of a railroad rail would make a layman

very doubtful of the feasibility of transporting rails of such lengths on

flat-cars except on a perfectly straight stretch of track. It appears to be so

rigid that it would seem impossible to bend it but actually there is sufficient

flexibility so that the rail will bend with the curvature of the track.

The ordinary rail length is 39 feet, so that in ordinary

track there are two rail joints for every 39 feet of track. These joints

represent the point of greatest wear in rail because each wheel which passes

from the end of one rail across the small gap to the beginning of the next,

strikes that next rail the equivalent of a heavy hammer blow. When tracks are

welded together it makes one continuous smooth surface and thus eliminates entirely

track joint maintenance and at the same time makes for very much smoother

riding track.

There are two methods of doing the welding job - by an

electric annealer or by the oxy-acetylene method, the latter being the latest

development and the method used bv the New Haven. The abutting rail ends are

heated to a temperature of about 2,280 degrees Farenheit, using a

mechanically-oscillated welding head that applies heat evenly to the rail sections

from all directions. Simultaneously with the application of heat, the rail ends

are forced together under a pressure which attains a maximum 2,500 pounds per

square inch

Next, in order to achieve a refinement of the grain of the

metal in the vicinity of the joint and to relieve internal stresses set up

during the welding procedure, the ioint is uniformly re-heated to the critical temperature

(about 1,380 degrees Farenheit) and allowed to cool in the atmosphere. In a

test of the strength of such welded rail, a load of 50,000 pounds was rolled back

and forth across the joint of a welded rail, supported as a cantilever, two million

times without any failure developing.

Other locations where welded rail of varying lengths is now in

service are Sackett's Point Road, Toelles crossing, Ward Street, Wallingford

station, Parker Street, Hosford Street, Lee's Crossing, Mooney's, Cooper Street,

Cherry Street, South Colony Street, Meriden station, Cross Street, Brittania

Street, North Colony Street, and Warehouse Point bridge, all on the Hartford Division.

1. A typical rail joint showing wear from constant impact of

wheels.

2. A finished weld.

3. Oxy-acetylene welding apparatus at work welding two

rails.

4. A close-up of the flames showing how they are brought to

bear on the rails from all directions at once.

5. The complete weld, before finishing and polishing.

6. Removing upset metal with Oxy-acetelyne cutting machine.

7. Grinding and polishing.

8. Finished rail loaded on flat cars.

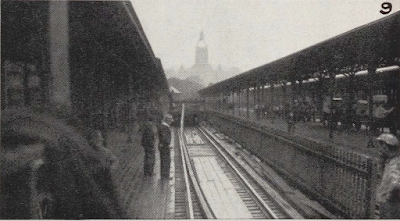

9 and 10. Unloading the rail where it is to be placed in

track, by means of pulling the flat cars out from underneath.

11. The other end is anchored so that engine can pull cars

out.

12. The finished job of continuous train at the Hartford station.

I was surprised to see that the New Haven was installing welded rail prior to WWII. I wonder how much more was finished by the end of the '40s, even with the war.

No comments:

Post a Comment